Date:

Ever wondered how groups of cells managed to build your tissues and organs while you were just an embryo?

Using state-of-the-art techniques he developed, UC Santa Barbara researcher Otger Campàs and his group have cracked this longstanding mystery, revealing the astonishing inner workings of how embryos are physically constructed. Not only does it bring a century-old hypothesis into the modern age, the study and its techniques provide the researchers a foundation to study other questions key to human health, such as how cancers form and spread or how to engineer organs.

“In a nutshell, we discovered a fundamental physical mechanismthat cells use to mold embryonic tissues into their functional 3D shapes,” said Campàs, a professor of mechanical engineering in UCSB’s College of Engineering who holds the Duncan & Suzanne Mellichamp Chair in Systems Biology. His group investigates how living systems self organize to build the remarkable structures and shapes found in nature.

Cells coordinate by exchanging biochemical signals, but they also hold to and push on each other to build the body structures we need to live, such as the eyes, lungs and heart. And, as it turns out, sculpting the embryo is not far from glass molding or 3D printing. In their new work,"A fluid-to-solid jamming transition underlies vertebrate body axis elongation," published in the journal Nature, Campàs and colleagues reveal that cell collectives switch from fluid to solid states in a controlled manner to build the vertebrate embryo, in a way similar to how we mold glass into vases or 3D print our favorite items. Or, if you like, we 3D print ourselves, from the inside.

Most objects begin as fluids. From metallic structures to gelatin desserts, their shape is made by pouring the molten original materials into molds, then cooling them to get the solid objects we use. As in a Chihuly glass sculpture, made by carefully melting portions of glass to slowly reshape it into life, cells in certain regions of the embryo are more active and ‘melt’ the tissue into a fluid state that can be restructured. Once done, cells ‘cool down’ to settle the tissue shape, Campàs explained.

“The transition from fluid to solid tissue states that we observed is known in physics as ‘jamming’,” Campàs said. “Jamming transitions are a very general phenomena that happens when particles in disordered systems, such as foams, emulsions or glasses, are forced together or cooled down.”

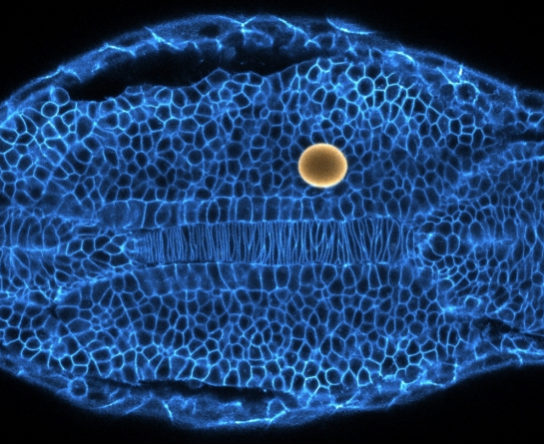

This discovery was enabled by techniques previously developed by Campàs and his group to measure the forces between cells inside embryos, and also to exert miniscule forces on the cells as they build tissues and organs. Using zebrafish embryos, favored for their optical transparency but developing much like their human counterparts, the researchers placed tiny droplets of a specially engineered ferromagnetic fluid between the cells of the growing tissue. The spherical droplets deform as the cells around them push and pull, allowing researchers to see the forces that cells apply on each other. And, by making these droplets magnetic, they also could exert tiny stresses on surrounding cells to see how the tissue would respond.

“We were able to measure physical quantities that couldn’t be measured before, due to the challenge of inserting miniaturized probes in tiny developing embryos,” said postdoctoral fellow Alessandro Mongera, who is the lead author of the paper.

“Zebrafish, like other vertebrates, start off from a largely shapeless bunch of cells and need to transform the body into an elongated shape, with the head at one end and tail at the other,” Campàs said. The physical reorganization of the cells behind this process had always been something of a mystery. Surprisingly, researchers found that the cell collectives making the tissue were physically like a foam (yes, as in beer froth) that jammed during development to ‘freeze’ the tissue architecture and set its shape.

These observations confirm a remarkable intuition made by Victorian-era Scottish mathematician D’Arcy Thompson 100 years ago in his seminal work “On Growth and Form.”

“He was convinced that some of the physical mechanisms that give shapes to inert materials were also at play to shape living organisms. Remarkably, he compared groups of cells to foams and even the shaping of cells and tissues to glassblowing,” Campàs said. A century ago, there were no instruments that could directly test the ideas Thompson proposed, Campàs added, though Thompson’s work continues to be cited to this day.

The new Nature paper also provides a jumping-off point from which the Campàs Group researchers can begin to address other processes of embryonic development and related fields, such as how tumors physically invade surrounding tissues and how to engineer organs with specific 3D shapes.

“One of the hallmarks of cancer is the transition between two different tissue architectures. This transition can in principle be explained as an anomalous switch from a solid-like to a fluid-like tissue state,” Mongera explained. “The present study can help elucidate the mechanisms underlying this switch and highlight some of the potential druggable targets to hinder it.”

Research on this project was conducted also by UCSB researchers Payam Rowghanian, Hannah J. Gustafson, Elijah Shelton, David A. Kealhofer, Emmet K. Carn, Friedheim Serwane, Adam A. Lucio and James Giammona.